2025 Summer Solstice Vineyard Tour: It's Been Average, Which Is Just Perfect

One month ago, I wrote about how we'd exited frost season and entered flowering in ideal conditions. Not too hot, not too cold, not too windy. Just... benign. I'm pleased to report that the last month warmed up, as you'd expect in late May and June, but stayed ideal for the season. Our average high has been 87.1°F, but no day has topped 97°F. Our average low has been 45.5°F but no night has gotten below 37.8°F. While every day has seen breezes into the teens, we haven't had a single 20mph gust. We're starting to get to the point where it's hot to be outside for a long time in the middle of the day, but we haven't had a heat wave and I've slept with my windows open and the AC off. It's honestly been glorious, and we're feeling lucky that it's this late in the year and we haven't yet seen any oppressive heat.

These conditions are ideal for grapevines to make rapid progress, and I decided to take a ramble around the vineyard this morning to document where we are. First, a look at a block of head-trained Grenache so healthy and vigorous that I challenge you to find the fruit tree in amongst these vines:

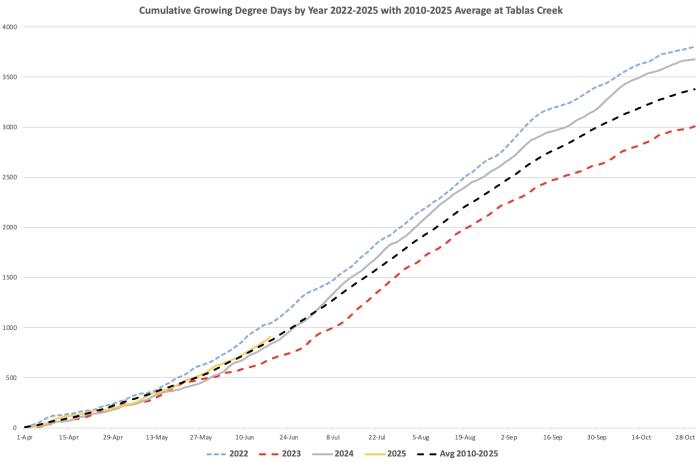

One of the most commonly used tools to measure a growing year is a term called Growing Degree Days, which is essentially a measurement of how many hours a location has seen above a certain threshold, typically indexed to the crop's growing needs and for grapevines around 50ºF. Comparing what we've seen this year to the last few years as well as our 2010-2025 average, you can see how down-the middle 2025 has been so far. Not as hot as 2022. Not as cool as 2023. A little warmer than 2024 was, though you'll see that at this time of year in 2024, it was about to get a lot hotter (by contrast, the weather over the next week or so looks like it will be staying moderate). The Degree Day data supports the idea that things have been average so far. And in this case, average is just perfect:

We're largely through flowering, even in our latest varieties, but there's a large variation in how much fruit development we've seen. This is totally normal for this time of year. Compare an early grape like Grenache (left) with Mourvedre (right), which one of our latest.

All the grapes will grow in size over the next month or so, until they squish together into a cluster. They actually reach peak mass at the moment of veraison, when they start to soften and accumulate sugar, and will end up losing about 10% of their mass between veraison and harvest.

At this point, what we're mostly looking for is vine health. And we're seeing great evidence of that everywhere. Check out these two vines, again Grenache on the left and Mourvedre on the right. Although Grenache is more robust, both look like they're bursting with vigor:

We're continuing our work to try to achieve our desired vine density in some of our blocks where we've lost vines over the years. I wrote a couple of years ago about our work with layering, where we bury canes from nearby vines and train them up into missing vine positions. Those canes then sprout roots where they were buried, while being supported by the parent vine. You can see a great example of how this works, in a Syrah block. The cane is coming from the parent vine, on the right, and reappearing in the formerly-missing vine position on the left. That child vine already has clusters on it. Our success in layering Syrah played an important role, we think, in the fact that it was one of the only varieties last year to see increased production compared to 2023:

A nearby head-trained, dry-farmed, no-till Counoise block that we planted in 2021 saw some vine loss from the late spring frosts we got in 2022. How do we establish new vines in a block that we aren't irrigating? We use the low-tech solution that helped us plant our Scruffy Hill block in 2005 and 2006: five-gallon buckets with holes drilled in the bottom. We fill those buckets as needed with a water truck, and that water then drips out, supporting the new vines without negatively impacting the development of the established vines nearby:

We're continuing to try experiments that will help us determine the right way to reduce tillage at Tablas Creek. Most of the studies that have studied no-till farming have been done in places wetter than Paso Robles, or at least in places where there is rainfall year-round. Here, it stops raining in April and doesn't rain again until November. That means that unless you irrigate, water is never replenished from above during the growing season, and you have to do everything you can to preserve what falls during the winter. No-till farming does a great job of preserving soil networks and building organic matter, but it does allow other plants to compete with our vines for the limited water resources. In one block we're now on our third year of an experiment that compares spading (so where we chop up the cover crop into the topsoil each spring), mowing (where we mow the cover crops, a few times if necessary, but otherwise leave the soil undisturbed), and crimping (where we bend over the cover crop but leave it in place as a mulch layer). Here you can see the boundary between the mown and spaded sections:

In a Cinsaut block nearby, we had exceptionally tall cover crop growth because it was so wet that we couldn't deploy our sheep there this winter without worrying it would turn into a compacted mud pit. So we decided to alternate crimped rows with spaded rows. It seems like, based on our early returns, that some sort of hybrid approach like this might make the most sense of all:

Adding to the hopefulness of the moment is the new growth we're seeing in a block that we grafted from Tannat (of which we have plenty) over to two whites that we always wish we had more of: Picardan and Clairette Blanche. Those grafts, completed about a month ago, are now bursting to life, powered by the 20-year-old roots. We're hopeful that we'll get production off the new material as soon as next year:

So, that's the report from the vineyard, as of mid-June. So far, so good. Next stop: veraison.