Sustainability, Hotel Towels, and the One Block Challenge

More than a decade ago, I wrote a blog I called Common Sense Sustainability in which I proposed that in order for a sustainability initiative to attain broad acceptance, it needed to be something that offered more than just the promise of a better world: it needed to help the bottom line. My example was the proliferation of notices hanging in hotel bathrooms that you, the guest, could help the hotel preserve the Earth's resources by reusing your towel more than once. From that blog's introduction:

Does the hotel really care about this, or just about the dollars they're saving in water, labor and soap? It's a Kimpton, so probably they do care. But many less environmentally-conscious hotels do the same thing, and I think that it's one of the best examples of a common-sense approach to sustainability that can, applied on a broad level, have enormous benefits to the use of resources without any noticeable detriment in customer experience.

While that might sound cynical, or at least jaded, I don't actually think that's the case. Resources, after all, have costs. Using fewer resources should in most cases cost a business less. We have found this to be true in ways large and small. A few examples that I've written about here on the blog include:

- Our use of stainless steel canteens instead of plastic water bottles in our tasting room. We estimate that this saves something like 15,000 plastic bottles from being created each year. While some walk away, and each canteen costs us about five times what a plastic water bottle would, the loss rate is only about 5% so our overall costs are reduced by 75%.

- Our move to pour our tasting room samples out of stainless steel kegs instead of bottles. We estimated that it took us only 9 months to pay back the initial investment in the kegs and the dispensers, and saves some 10,000 bottles per year from needing to be made, shipped, filled, emptied, and recycled. The decision has additional benefits in wine freshness, reliability, and reduced waste.

- Our use of lightweight glass since 2010, which I estimated back in 2023 had saved us some $2.2 million over the previous 14 years while also reducing our total carbon footprint by about 10%. Then, if we needed further evidence, in late 2023 we received news that the glass plant that had been making our lightweight bottles was closing. We found another vendor who had in the intervening 15 years improved the technology further and was able to make beautiful bottles at 390 grams instead of the already-light 450 we'd been using. Those new bottles came at a savings that came to an additional $100,000 per year.

- Even our foray into boxed wine, which began with a desire to explore the 84% reduction in carbon footprint that each box provides over the four bottles it replaces, and was bolstered by the benefits in freshness and convenience we came to realize it offers its users, comes with a lower cost. One box and one bag cost us about third of what the four bottles, labels, and closures cost. We're able to use that savings to offer customers a better price on the wine.

You'll notice that the examples above are mostly about packaging, and not our vineyard. We are still committed to making strides in sustainability there too, though we think that the main benefit to sustainability investments like our long-standing commitment to organic farming, our only slightly less long-standing belief in dry-farming, and our more recent moves into biodynamic and regenerative farming are mostly about wine quality and long-term vineyard health (as well as the health of our team) rather than savings. We're not alone; a well-publicized study found in 2021 that organic and biodynamic wines were rated more highly by major reviewers.

That said, there are savings to be found there, or at least tradeoffs that make the additional costs less costly. In general, with these more holistic approaches to farming, you're trading input costs for labor costs. Our flock of sheep has meant that we haven't had to bring in outside fertilizer since before Covid. The owl boxes, insectaries, and habitat we're building means that we can go without (or with less) manual trapping or the sprays that conventional vineyards use to control pests. That comes with savings; after all, it's not as though Monsanto and their brethren are in business out of the goodness of their hearts. They are making profits on the chemicals that vineyards buy and use.

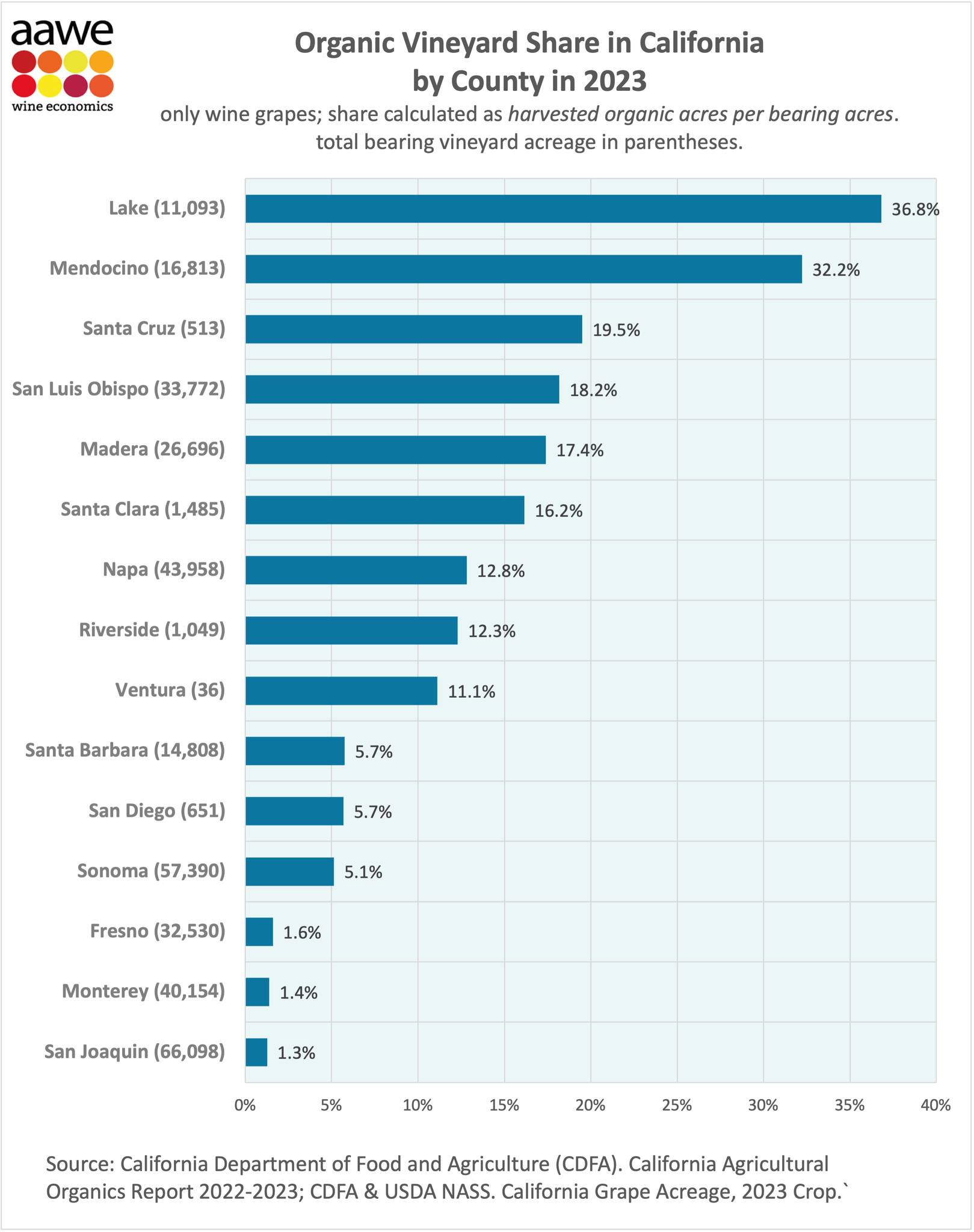

But while we have felt that the tradeoffs in wine quality, vineyard health, and our team's working environment are worth the extra labor costs, we're still in the definite minority. A chart shared by the American Association of Wine Economists shows that only 9.3% of California vineyard acres were certified organic in 2023:

If under 10% of California vineyards are organic, a significantly smaller percentage is certified Biodynamic or Regenerative. This is why I am so impressed and encouraged by the momentum behind a new initiative from the Regenerative Viticulture Foundation (RVF) called the One Block Challenge™. This initiative, according to their website, aims "to enable growers to try out regenerative practices in a secure way, without ‘betting the farm’ on the outcome." The first trial launched in Paso Robles in January 2025 and has since expanded to South Africa, New Zealand, Napa, Texas, and the UK. It will be launching in France soon, and in more regions next year. Hundreds of wineries have participated, a number that dwarfs the total that have certified with any existing regenerative certification in the five years since they launched.

The idea follows the journey that Robert Hall Winery, a fellow Paso Robles producer owned by O'Neill Family Vintners, has been following over the past few years. Under the leadership of Caine Thompson (who not coincidentally was also asked to serve as a trustee of the RVF), Robert Hall converted one of its blocks to regenerative farming back in 2020 and found measurable improvements in easily understandable metrics. Caine shares his experience on the RVF website:

"we’ve seen our vines become healthier, more resilient to climate stress, and significantly more drought-tolerant. The fruit quality has improved noticeably—there’s less dehydration and shrivel, resulting in a purer fruit character that more clearly expresses the terroir of the site, soil, and season, especially when compared to adjacent vines grappling under extreme climate conditions."

Equally importantly, they found that these improvements came without significant increases in per-ton farming costs. In an article published by the San Francisco Chronicle in 2022, Caine reports a lower cost per ton in the block that they converted to regenerative farming versus the block that is farmed conventionally:

"He calculated that regenerative farming costs 10% more than conventional farming at his vineyard — $6,833 per acre per year for regenerative compared with $6,204 for the control block. But because of the regenerative vines’ higher yields, the farming cost per ton of grapes was actually 4% lower."

When I reached out to him to ask about the success of the One Block Challenge, Caine highlighted the community nature of the approach:

"the initiative is set up as a community driven project with a lot of peer-to-peer support from community members and pioneers like yourselves and other ROC certified wineries. This helps stop tribalism by not making it about one company, or one certification which can feel daunting, but instead simply outlies the philosophy and key practices to start implementing."

I love this photo, from the One Block Challenge website, with our former Viticulturist Jordan Lonborg in the baseball cap on the right and our current Regenerative Specialist Erin Mason in the overalls across the circle from him:

I asked RVF co-founder and Chair of the Board Stephen Cronk (also proprietor at Maison Mirabeau in Provence, the first Regenerative Organic Certified vineyard in France) why he thought that the One Block Challenge had seen such broad support so fast, and he had several thoughts. At its core, he said that he thought it had been successful in part because it has been "meeting winegrowers precisely where they are, without judgement—inviting them to trial regenerative practices on a single block, be it a row, an acre, or any parcel of their choosing, for just one year." He also pointed out something that I've always appreciate about the regenerative approach: that it's modern and empirical: "Crucially, the 1BC places a strong emphasis on measurable outcomes. Growers are encouraged to take baseline measurements and monitor progress, building confidence through evidence rather than ideology."

Back to the hotel towel example. If groups like the RVF and initiatives like the One Block Challenge can show wineries that farming regeneratively offers the opportunity to make better fruit at a similar or even lower price, it has a chance to be adopted widely and fast, and not just by the vineyards who are true believers in the importance of using their farming to make a better world. And that is critical if we want regenerative farming to achieve one of its principal goals: to set up agriculture as a part of the solution rather than a part of the problem to some of the world's more pressing challenges. These include resource scarcity, climate change, topsoil loss, and inequality. Given that 31% of the Earth's landmass is used for agriculture and this work involves 27% of its population, the potential impact is vast. More importantly, these challenges are probably not solvable without agriculture's contribution.

Let's raise a glass to common sense sustainability initiatives, from hotel towels to the One Block Challenge.