The disconnect between what shipping costs and what people think shipping costs has never been greater

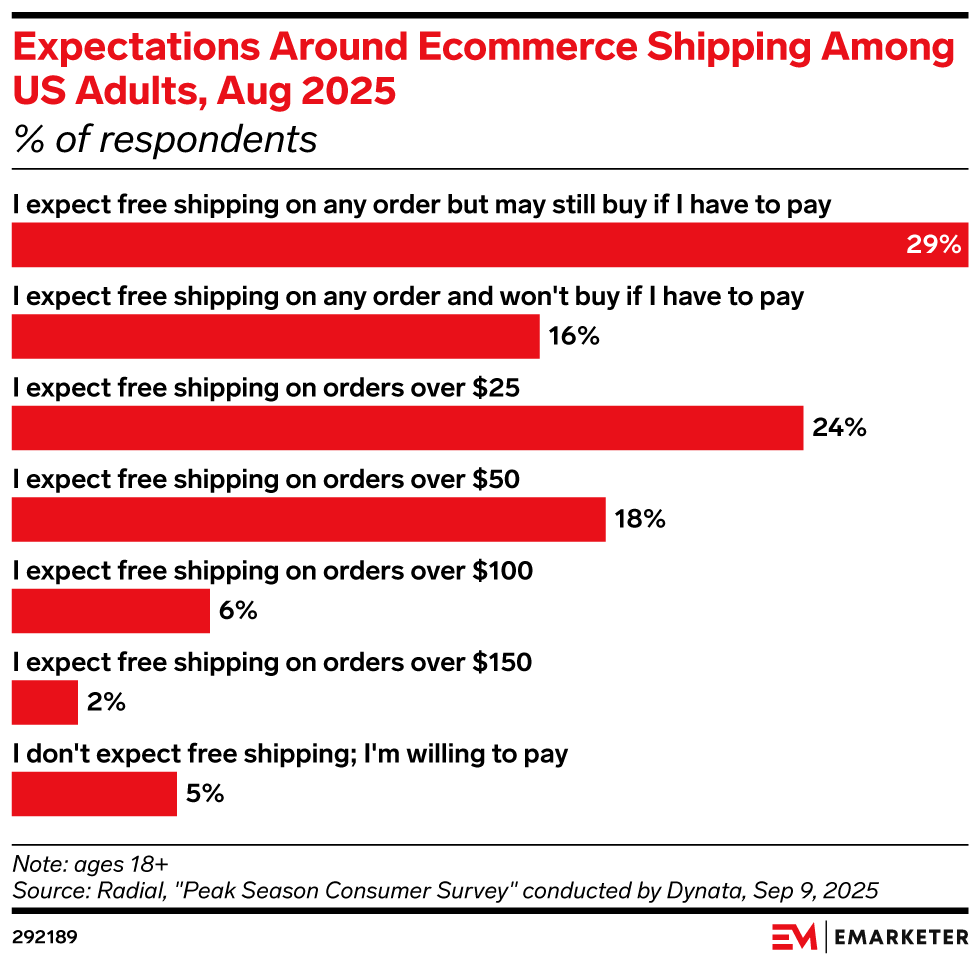

A study published last year reported that 45% of American consumers expect free shipping on any order. Another 42% expected it on orders over $50. Just 5% expected to pay for shipping on orders of any size. That's sobering for anyone in the wine business.

I recently got involved in a Facebook discussion about the barriers to entry that wineries place between their products and their customers. While the discussion started with commenters lamenting the rising costs of tasting fees and the hurdle that places between new consumers and a wine country experience, the complaints morphed pretty quickly into other barriers to purchase, most notably shipping fees. The general feeling among the commenters was that because people have become so accustomed to free shipping, wineries need to do the same if they want to remain competitive.

There is ample evidence that Amazon and the companies who have followed its lead have trained American consumers to expect free shipping. A study published by EMarketer last year reported that 45% of American consumers expect free shipping on any order. Another 24% expected it on orders over $25. 18% more expected it on orders over $50. Just 5% expected to pay for shipping on orders of any size. The chart is sobering for anyone in the business of shipping heavy, perishable items around the country:

There is psychology at work here. People hate feeling nickeled and dimed, and studies have shown that each time you make people think about an added cost you lose a (surprisingly high) percentage of their sales.

Of course, the free shipping that Amazon offers isn't really free; it's subsidized by Prime membership fees and only possible because the company's massive scale has allowed them to build their own distribution network with roughly 175 fulfillment centers near most of their American customers and with their own fleets of trucks, planes, and robots. Not to mention the human costs (representative reporting here, here and here) of Amazon's ruthless push to maximize efficiency.

Amazon knows well that its embrace of free shipping has given it a competitive advantage. That is true in part because shipping is really expensive, and has gotten a lot more so over the past few years. Since 2019, UPS and FedEx have implemented general price increases each year to the cumulative total of 47.9%. They have also added (or increased) fuel surcharges, adult signature surcharges, and residential delivery surcharges. We work with a fulfillment house that has the volume and clout to negotiate much better rates with the shippers than we could get off the shelf. We also use some of the lightest bottles available, which means that a case of our wine can be 10 pounds or more lighter than many premium wineries would face. Even so, our shipping cost to ship a 6-bottle package 2nd-day air to the east coast is around $80. Add a 19% fuel surcharge and we're paying over $95. A full case costs us around $165. Ground shipping is much less exorbitant, but it's still not cheap. Sending six bottles within California costs us about $37 with the fuel surcharges, and a case costs us about $48. That same case to the east coast costs us about $75. In total, we spent just over a million dollars on shipping last year, which was almost 10% of our total revenue.

One of the suggestions that came out of the Facebook discussion was for wineries just to build the price of shipping into the cost of their wines and reduce the friction of people seeing a charge that might make them pause at checkout. And sure, if a winery is direct-to-consumer only and relatively high priced. If you're selling a $70 bottle of wine DTC and charging for shipping, you're probably better off raising the price to $80 and including shipping. After all, if you're a 100% DTC winery, you’re mostly competing against yourself. If your overall value proposition is solid, building the cost of shipping into your list price probably isn't going to meaningfully turn people away. I'm not sure the same thing holds true if you're selling $25 bottles of wine. At that point, raising your prices to $35 to include shipping is a 40% increase! It's worth also noting that if you raise your prices to include shipping, you're penalizing (or at least making more money off) the customers who come to visit your tasting room and carry the wine out with them. It's no wonder that the average price of a wine shipped DTC in America is over $55; the economics of shipping under-$30 bottles are challenging.

It's a more complicated calculation if your wines are also in the wholesale market. A winery that doesn't feel comfortable passing along shipping costs to their customers has three options, as I see it, none of them super appealing:

- You can raise your direct-to-consumer price to include shipping but leave your wholesale prices the same. Doing so means you know that the retail price of your wines out in the market is going to be lower than your direct customers will get. That’s not a great way of making your direct customers feel valued, because there's not a faster way to make a wine club member into an ex-member than for them to find the wines they've bought from you cheaper at retail near where they live.

- You can raise all your prices to a level where you absorb the shipping costs in your margins. That might have worked in 2021, but is not an attractive one right now. The weakness of the wine market means that you’d likely lose a chunk of your direct customers and probably an even larger chunk of your wholesale business, as that side of the business is particularly price sensitive at the moment.

- You could just eat the cost of the shipping in your margins. What does that cost look like for a winery like Tablas Creek? We sell about $8 million in wine each year to our direct customers. About $2.5 million of that goes out of our tasting room, so no shipping necessary. To ship the 21,000 packages containing the remaining $5.5 million in wine, we pay something like $1 million in shipping fees. If we just ate those costs, it would put us out of business within a couple of years.

How much would we have to raise our prices to cover those shipping costs? If we didn’t lose any sales (not likely) the 18.2% increase to bring that $5.5 million to $6.5 million would mean that a wine like our Esprit de Tablas would go from $75 to $88.60. Our Grenache would go from $45 to $53.20. Our Patelin de Tablas would go from $30 to $35.50. And, of course, we would lose sales. The Patelin de Tablas is particularly price sensitive, as it’s a wine that much of is poured by-the-glass at restaurants. Raising it 18% in wholesale would likely result in us losing more than 50% of the sales. You can see the challenge.

So, what is a winery to do? At Tablas Creek we’ve tried to do a handful of things:

- We’ve largely moved to shipping ground, while giving our customers options. A few years ago, we moved from shipping ground within California and 2nd-day air outside California to shipping ground everywhere. We show the actual shipping cost (minus the fuel surcharge) and let people make their own choice as to which form of shipping they want to use. We also watch the weather diligently, and intervene to suggest people delay or reroute their shipments if it looks like they'll pass through arctic cold or sustained heat.

- We’ve taken advantage of remote warehouses to lower shipping costs. For the last several years, we've worked with a fulfillment house that has satellite warehouses in Missouri and New York. For our wine club members east of the Rockies, we've shipped the wine (palletized) to these satellite warehouses, from where they can be packed to go ground and arrive in one, two, or (occasionally) three days, instead of four or five from California. That's less expensive for the customers and better for the wine. Of course, there are costs, both monetary and logistical, of having to get our wine to the other warehouses and then to managing the scattered inventory.

- We’ve offered good discounts to our club members that mean that even with shipping they usually come out ahead. Our VINsider Wine Club members get 20% off on any orders, and 25% on case orders. That means that even if they have to pay $60 shipping to get a case of wine to the East Coast, their discount on that wine is typically between 150% and 200% of the shipping cost.

- We’ve been transparent with our customers. Instead of putting round numbers on our shipping charges, we share the actual shipping that we pay. We want people to know that we're not making money on their shipping. It's more complicated to explain than just saying "$50/case to the east coast" but I think it builds trust.

- We’ve used shipping promotions to incentivize certain kinds of sales. By having shipping be a part of our "normal" operating procedures, we've been able to use shipping promotions to good effect. A few of those that we've done over recent years have been:

- The $10 flat-rate shipping we've done in April

- Building our holiday packs to include $10 shipping

- Rewarding anyone who places an order that includes six or more bottles of our flagship Esprit de Tablas, Esprit de Tablas Blanc, or Panoplie with $10 flat-rate shipping on their entire order

- We eat some of the cost. We've chosen not to pass along the fuel surcharges. Somehow, the difference between $60 to ship a case of wine to the east coast and $75 feels significant. Between that subsidy and the cost of the shipping promotions, we ended up last year covering about $350,000 of the $1 million that we were charged for shipping. That's something that we've decided we can absorb, especially if it incentivizes sales that we think are particularly high value, such as those of our higher-end wines, or those of gifts to potential new customers.

Is what we’re doing the right approach? I’m not sure. I have no doubt that we’re losing some add-on sales because people get to our checkout screen and decide it isn’t worth it to spend $60 to get a case of wine across the country. I’m sure that seeing the $35 shipping on every semi-annual club shipment is something of a drag on our wine club membership. But is it a $1 million drag? I doubt it. If you're a patron of (or an employee of) a winery that you think is doing this well, I'd love you to share in the comments.

Ultimately, we hope that people see the value in the wines that we make, and the benefits of the programs that we do offer. After all, nothing comes for free. Even free shipping.